OR

THE SPEECH OF FLOWERS.

LONON [sic],

PRINTED FOR JOHN STAFFORD, AND ARE TO

BE SOLD AT HIS HOUSE, AT THE GEORGE AT

FLEET-BRIDGE.

1655.

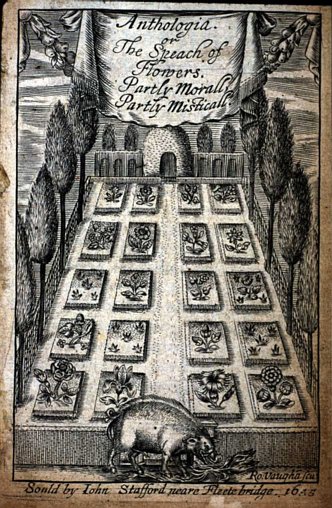

Anthologia.

Or

The Speach of Flowers.

Partly Morall,

Partly Misticall.

Ro: Vaughan scu:

Sould by Iohn Stafford neare Fleete bridge, 1655

WILLIAM STAFFORD, ESQUIRE,

MERCHANT OF BRISTOL.

Worthy Sir,

IN this plundering age, wherein the studies of so many have been ransacked, and many papers intended for private solace and contentment have bin exposed to publike view, it is my fortune to light on the ensuing discourse: It seemed to me pitty that it should be strangled in obscurity, as conceiving it might conduce something to the delight of the Reader, for surely no ingenuous person can be so constantly serious, yea surly and Criticall, but to allow some intervalls of refreshment not onely as lawfull but necessarie.

Let such morose, yea mischievous spirits pine themselves to walking Anatomies, who brand all refection of the mind by ludicrous intermissions to be unlawfull, to spare an heavier censure (which may more resent of anger) the worst I wish them is alwaies to eate their meate without sauce, and let them try whether their palate will be pleased with the gust thereof.

In the following discourse there is nothing presented but sweet Flowers and herbs: I could wish it had been in the summertime, when the heate of the Sunne might have improved their fragrancie to the greatest advantage and rendred them more acceptable to the smell of the Reader: Being now sadly sensible that Autumne the Usher of Winter will abate of their sweetnesse, and present them much to their loss.

Sure I am no bitter Colloquintida appeareth in this our Herball; I meane no tart and toothed reflections on any. Dull are those witts which cannot make some smile, except they make others cry, having no way to worke a delight and complacency in the Reader, save onely by gashing, wounding and abusing the credits of others.

It is desired, that this discourse may but finde as much candidness as it brings, and be entertained according to his own innocency. I have heard a storie of an envious man, who had no other way to be revenged of his Neighbour, who abounded with store of Bee-hives, then by poysoning all the Flowers in his own Garden wherein his Neighbours Bees tooke their constant repast, which infection caused a generall mortality in all the winged cattell of his Neighbour.

I hope none have so spleneticke a designe against this my harmelesse Treatise, as to invenome my flowers with pestilent and unintended interpretations, as if any thing more then flowers were meant in the flowers, or as if they had so deepe a root under ground, that men must mine to understand some concealed and profound mysterie therein, surely this Mythologie is a Cabinet which needeth no key to unlock it, the lid or cover lyeth open.

Let me intreate you Sir to put your hand into this Cabinet, and after therein you finde what may please or content you, the same will be as much contentment unto your

| True Friend, J. S. |

OR

THE SPEECH OF FLOWERS.

There was a place in Thessaly (and I am sorry to say there was a place in Thessaly, for though the place be there still, yet it is not it selfe. The bones thereof remain, not the Flesh and Colour. The standards of Hilles and Rivers, not the Ornaments of Woods, Bowers, Groves and Banqueting-houses. These long [2] since are defaced by the Turkes, whose barbarous natures wage war with civility it selfe, and take a delight to make a Wildernesse where before their conquest they found a Paradise.)

This place is some five miles in length, and though the breadth be Corrival with the length, to equallize the same, and may so seeme at the first sight; yet it falleth short upon exact examination, as extending but to four miles. This place was by the Poets called Tempe, as the Abridgment of Earthly happinesse, showing that in short hand, which the whole world presen[3]ted in a larger character, no earthly pleasure was elsewhere afforded, but here it might be found in the height thereof.

Within this Circuit of ground, there is still extant, by the rare preservation of the owner, a small Scantlin of some three Acres, which I might call the Tempe of Tempe, and re-epitomiz'd the delicacies of all the rest. It was divided into a Garden, in the upper Part whereof Flowers did grow, in the lower, Hearbs, and those of all sorts and kinds. And now in Spring time earth did put on her new clothes, though had some cunning Herasld beheld the same, [4] he would have condemned her Coat to have been of no antient bearing, it was so overcharged with variety of Colours.

For there was yellow Marigolds, Wallflowers, Auriculusses, Gold knobs, and abundance of other namelesse Flowers, which would pose a Nomenclator to call them by their distinct denominations. There was White, the Dayes Eye, white roses, Lillyes, &c., Blew Violet, Irisse, Red Roses, Pionies, &c. The whole field was vert or greene, and all colours were present save sable, as too sad and doleful for so merry a meeting. All the Children of Flora being summoned [5] there, to make their appearance at a great solemnity.

Nor was the lower part of the ground lesse stored with herbs, and those so various, that if Gerard himselfe had been in the place, upon the beholding thereof, he must have been forced to a re-edition of his Herball, to add the recruit of those Plants, which formerly were unseen by him, or unknown unto him.

In this solemn Rendevouz of Flowers and Herbs, the Rose stood forth, and made an Oration to this effect.

It is not unknown to you, how I have the precedency of [6] all Flowers, confirmed unto me, under the Patent of a double Sence, Sight, smell. What more curious Colours? how do all Diers blush when they behold my blushing, as conscious to themselves that their Art cannot imitate that tint which Nature hath stamped upon me. Smell, it is not lusciously offensive, nor dangerously Faint, but comforteth with a delight, and delighteth with the comfort thereof: Yea, when Dead, I am more Soveraigne then Living: What Cordials are made of my Syrups? how many corrupted Lungs (those Fans of Nature) sore wasted with consumption, [7] that they seem utterly unable any longer to cool the heat of the Heart with their ventilation, are, with Conserves made of my stamped Leaves, restored to their former soundnesse again: More would I say in mine own cause, but that happily I may be taxed of pride and selfe-flattery, who speak much in mine own behalf, and therefore I leave the rest to the judgment of such as hear me, and passe from this discourse to my just complaint.

There is lately a Flower (shal I call it so? In courtesie I will tearme it so, though it deserve not the appellation), a Toolip, which hath ingrafted the love [8] and affections of most people unto it; and what is this Toolip? A wellcomplexion'd stink, an ill savour wrapt up in pleasant colours. As for the use thereof in Physick, no Physitian hath honoured it yet with the mention, nor with a Greek, or Latin name, so inconsiderable hath it hitherto been accompted; and yet this is that which filleth all Gardens, hundreds of pounds being given for the root thereof, whilst I the Rose, am neglected and contemned, and conceived beneath the honour of noble hands, and fit only to grow in the gardens of Yeomen. I trust the remainder to your [9] apprehensions, to make out that, which grief for such undeserved injuries will not suffer me to expresse.

Hereat the Rose wept, and the dropping of her white tears down her red cheeks, so well becomed her, that if ever sorrow was lovely, it then appeared so, which moved the beholders to much compassion, her Tears speaking more then her tongue in her own behalfe.

The Toolip stood up insolently, as rather challenging then craving respect, from the Common-wealth of Flowers there present, & thus vaunted it selfe.

I am not solicitous what to [10] returne to the Complaint of this Rose, whose own demerit hath justly outed it self of that respect, which the mistaken world formerly bestowed upon it, and which mens eyes, now opened, justly reassume, and conferre on those who better deserve the same. To say that I am not more worthy then the Rose, what is it, but to condemne mankind, and to arraign the most Gentle and knowing among men, of ignorance, for misplacing their affections: Surely Vegetables must not presume to mount above Rationable Creatures, or to think that men are not the most compe[11]tent judges of the worth and value of Flowers. I confess there is yet no known soveraign vertue in my leaves, but it is injurious to inferre that I have none, because as yet not taken notice of. If we should examine all, by their intrinsick valews, how many contemptible things in Nature would take the upper hand of those which are most valued; by this argument a Flint-stone would be better then a Diamond, as containing that spark of fire therein, whence men with combustible matter may heat themselves in the coldest season: and clear it is, that the Load-stone [12] (that grand Pilot to the North, which findeth the way there in the darkest night) is to be preferred before the most orient Pearle in the world: But they will generally be condemned for unwise, who prize things according to this proportion.

Seeing therefore in stones and minerals, that those things are not most valued, which have most vertue, but that men according to their eyes and fancies raise the reputation thereof, let it not be interpreted to my disadvantage, that I am not eminently known for any cordiall operation; perchance the discovery hereof is reserved for [13] the next age, to find out the latent vertue which lurketh in me. And this I am confident of, that Nature would never have hung out so gorgious a signe, if some guest of quality had not been lodged therein; surely my leaves had never been feathered with such variety of colours (which hath proclaimed me the King of all Lillies) had not some strange vertue, whereof the world is yet ignorant, been treasured up therein.

As for the Rose, let her thank her selfe, if she be sensible of any decay in esteem, I have not ambitiously affected superiority above her, nor have I fraudulent[14]ly endeavoured to supplant her: only I should have been wanting to my selfe, had I refused those favours from Ladies which their importunity hath pressed upon me: And may the Rose remember, how she, out of causelesse jealousie, maketh all hands to be her enemies that gather her; what need is there that she should garison her selfe within her prickles? why must she set so many Thornes to lye constant perdue, that none must gather her, but such as suddenly surprize her; and do not all that crop her, run the hazard of hurting their fingers: This is that which hath weaned the [15] world from her love, whilst my smooth stalk exposing Ladies to no such perills, hath made them by exchange to fix their removed affections upon me.

At this stood up the Violet, and all prepared themselves with respectful attention, honouring the Violet for the Age thereof, for, the Prim Rose alone excepted, it is Seignior to all the Flowers in the year, and was highly regarded for the reputation of the experience thereof, that durst encounter the cold, and had passed many bitter blasts, whereby it had gained much wisdome, and had procured a venerable respect, both to his person and Counsell.

[16] The case (saith the Violet) is not of particular concernment, but extendeth it selfe to the life and liberty of all the society of Flowers; the complaint of the Rose, we must all acknowledge to be just and true, and ever since I could remember, we have paid the Rose a just tribute of Fealty, as our Prime and principall As for this Toolip, it hath not been in being in our Garden above these sixty years: Our Fathers never knew that such a Flower would be, and perhaps our children may never know it ever was; what traveller brought it hither, I know not; they say it is of a [17] Syrian extraction, but sure there it grew wild in the open fields, and is not beheld otherwise, then a gentler sort of weed: But we may observe that all-forraign vices are made vertues in this countrey, forraign drunkennesse is Grecian Mirth (thence the proverb. The merry Greek), forraign pride, Grecian good behaviour; forraign lust, Grecian love; forraign lazinesse, Grecian harmelessnesse; forraign weeds, Grecian Flowers. My judgment therefore is, that if we do not speedily eradicate this intruder (this Toolip) in process of time will out us all of our just possessions, seeing no [18] Flower can pretend a clearer title then the Rose hath; and let us everyone make the case to be his owne.

The gravity of the Violet so prevailed with the Senate of Flowers, that all concurred with his judgment herein: and such who had not the faculty of the fluentnesse of their tongues to express themselves in large Orations, thought that the well managing of a yea, or nay, spoke them as well wishing to the general good as the expressing themselves in large Harrangues; and these soberly concluded, that the Toolip should be rooted out of the [19] Garden, and cast on the dunghill, as one who had justly invaded a place not due thereunto, and this accordingly was performed.

Whilst this was passing in the upper house of the Flowers, no less were the transactions in the lower house of the herbs; where there was a generall acclamation against Wormewood , the generality condemning it, as fitter to grow in a ditch, then in a Garden. Wormewood hardly received leave to make its own defence, pleading in this manner for its innocency.

I would gladly know whom I have offended in this com[20]mon-wealth of Herbs, that there should be so generall a conspiracy against me? only two things can be charged on me, commonnesse and bitternesse; if commonnesse pass for a fault, you may arraign Nature it selfe, and condemn the best Jewels thereof, the light of the Sun, the benefit of the Ayre, the community of the Water; are not these staple commodities of mankind, without which, no being or subsistance; if therefore it be my charity to stoop so low as to tender my selfe to every place, for the public service, shall that for which, if I deserve not praise I need no [21] pardon, be charged upon me as an offence.

As for my bitternesse, it is not a malicious and mischievous bitternesse to do hurt, but a helpfull and medicinall bitternesse, whereby many cures are effected. How many have surfeited on honey? how many have dig'd their gravs in a Sugar-loaf? how many diseases have bin caused by the dulcor of many luscious sweet-meats? then am I sent for Physitian to these patients, and with my brother Cardus (whom you behold with a loving eye, I speak not this to endanger him, but to defend my selfe) restore them (if temperate in any de[22]gree, and perswaded by their friends to tast of us) unto their former health. I say no more; but were all my patients now my pleaders, were all those who have gained health by me, present to intercede for me, I doubt not but to be reinstated in your good opinions.

True it is, I am condemned for over-hot, and too passionate in my operation; but are not the best natures subject to this distemper? is it not observed that the most witty are the most cholerick? a little over-doing is pardonable, I will not say necessary in this kind; nor let me be condemned as destru[23]ctive to the sight, having such good opening and abstergent qualities, that modestly taken, especially in a morning, I am both food and Physick for a forenoon.

It is strange to see how passion and selfe-interest sway in many things, more then the justice and merit of a cause; it was verily expected that Worm-wood should have been acquitted, and readmitted a member in the society of Herbs: But what will not a Faction carry; Worme-woods friends were casually absent that very day, making merry at an entertainment; her enemies (let not that Sex be angry for [24] making Wormwood feminine) appeared in a full body, and made so great a noise, as if some mouths had two tongues in them; and though some engaged very zealously in Wormwoods defence, yet, over-charged with the Tyranny of Number, it was carried in the Negative, that Wormwood , alias absynthium, should be pluckt up root and branch from the Garden, and thrown upon the Dunghill, which was done accordingly, where it had the wofull Society of the Toolip, in this happy, that being equally miserable, they might be a comfort the one to the other, and spend many [25] howers in mutuall recounting their several calamities, thinking each to exceed the other in the relation thereof.

Let us now amidst much sadness interweave something of more mirth and pleasantnesse in the Garden, There were two Roses growing upon one Bush, the one pale and wan with age, ready to drop off, as usefull only for a Still; the other a young Bud, newiy loosened from its green swadling clothes, and peeping on the rising Sun, it seem'd by its orient colour to be died by the reflection thereof.

Of these, the aged Rose thus began.

[26] Sister Bud, learn witt by my woe, and cheaply enjoy the free and ful benefit of that purchase which cost me dear and bitter experience: Once I was like your selfe, young and pretty, straitly laced in my green-Girdle, not swoln to that breadth and corpulency which now you behold in me, every hand which passed by me courted me, and persons of all sorts were ambitious to gather me: How many fair fingers of curious Ladies tendered themselves to remove me from the place of my abode; but in those daies I was coy, & to tell you plainly, foolish, I stood on mine own defence, [27] summoned my life-guard about me, commanded every prickle as so many Halberdeers, to stand to their Armes, defie those that durst touch me, protested my selfe a votary of constant virginity; frighted hereat, passengers desisted from their intentions to crop me, and left me to enjoy the sullen humour of my own reservednesse.

Afterwards the Sun beams wrought powerfully upon me, (especially about noon-time) to this my present extent, the Orient colour which blushed so beautifull in me at the first, was much abated, with an over- mixture of wanness and paleness [28] therewith, so that the Green (or white sicknesse rather, the common pennance for over-kept virginity) began to infect me, and that fragrant sent of mine, began to remit and lessen the sweetnesse thereof, and I daily decayed in my natural perfume; thus seeing I daily lessened in the repute of all eyes and nostrills, I began too late to repent my selfe of my former frowardnesse, and sought that my diligence by an after-game, should recover what my folly had lost; I pranked up my selfe to my best advantage, summoned all my sweetnesse to appear in the height thereof, recruit[29]ed my decayed Colour, by blushing for my own folly, and wooed every hand that passed by me to remove me.

I confesse in some sort it offers rape to a Maiden modesty, if forgetting their sex, they that should be all Ears, turn mouthes, they that should expect, offer; when we women, who only should be the passive Counterparts of Love, and receive impression from others, boldly presume to stamp them on others, and by an inverted method of nature, turn pleaders unto men, and wooe them for their affections. For all this there is but one excuse, and [30] that is absolute necessity, which as it breaks through stone- walls, so no wonder if in this case it alters and transposes the Sexes, making women to man it in case of extremity, when men are wanting to tender their affections unto them.

All was but in vaine, I was entertained with scorne and neglect, the hardened hands of dayly Labourers, brawned with continuall work, the black hands of Moores, which always carry Night in their Faces, sleighted and contemned me; yea, now behold my last hope is but to deck and adorn houses, and to be laid as a propertie [31] in windowes, till at last I die in the Hospitall of some still, where when useless for anything else, we are generally admitted. And now my very leaves begin to leave me, and I to be deserted and forsaken of my selfe.

O how happy are those Roses, who are preferred in their youth; to be warme in the hands and breasts of faire Ladies, who are joyned together with other flowers of severall kinds in a Posie, where the generall result of sweetnesse from them all, ravisheth the Smel by an intermixture of various colours, all united by their stalks within the same thred that bind[32]eth them together.

Therefore Sister Bud grow wise by my folly, and know, it is far greater happinesse to lose thy Virginity in a good hand, then to wither on the stalk whereon thou growest: accept of thy first and best tender, lest afterwards in vaine thou courtest the reversion of fragments of that feast of love, which first was freely tendred unto thee.

Leave we them in their discourse, and proceed to the relation of the Toolip and Wormwood , now in a most pitifull condition, as they were lying on the Dunghill; behold a vast Giant Boar comes unto them; [33] that which Hercules was said to kill, and which was accounted by some the foreman of the jury of his Lahours, was but a Pygmie, or rather but a Pig, in comparison of this; and with his Tusks wherewith Nature had armed him to be his sword, as his shoulders are his shield, he began to rend and tear the Toolip and Wormewood , who exclaimed unto him as followeth:

SIR,

Pitty useth alwaies to be an attendant of a generous mind, & valiant spirit, for which I have heard you much commended. Cruelty is commonly observed to keep company with Coward[34]linesse, and base minds to triumph in cruell actions, behold we are the objects rather of your pitty, whose sufferings may rather render us to the commiseration of any that justly consider our case. I the Toolip, by a faction of Flowers, was outed of the Garden, where I have as good a right and title to abide as any other; and this Wormewood , notwithstanding her just and long plea, how usefull and cordiall she was, was by a conspiracy of Herbs excluded the Garden, and both of us ignominiously confined to this place, where we must without all hopes quickly expire: Our [35] humble request unto you is not to shorten those few minutes of our lives which are left unto us, seeing such prejudice was done to our Vitals (when our roots were mangled by that cruel eradication) that there is an impossibility of our long continuance: Let us therefore fairly breathe out our last breath, and antidate not our misery, but let us have the favour of a quiet close and conclusion.

But if so be that you are affected with the destruction of flowers and herbs, know the pleasure and contentment therein must be far greater to root out [36] those which are fairly flourishing in their prime, whereof plenty are in this Garden afforded; and if it please you to follow our directions, we will make you Master of a Passe, which without any difficulty shall convey you into the Garden; for though the same on all sides almost is either walled or paled about, yet in one place it is fenced with a Hedge only, wherein, through the neglect of the Gardiner, (whose care it ought to be, to secure the same) there is a hole left in such capacity, as will yeeld you an easie entrance thereinto. There may you glut your selfe, and satiate your [37] soule with variety of Flowers and herbs, so that an Epicure might have cause to complain of the plenty thereof.

The Boar apprehends the motion, is sencible it was advantageous for him, and following their directions, he makes him selfe Master of his own desire. O the spitefulnesse of some Natures! how do they wreck their anger on all persons: It was [no] revenge for the Toolip and Wormwood , unless they had spitefully wronged the whole Corporation of Flowers, out of which they were ejected as uselesse and dangerous Memhers: And now consider, how these [38] two pride themselves in their own vindicative thoughts? how do they in their forerunning fancy antidate the death of all Herbs and Flowers. What is sweeter then revenge? how do they please themselves to see what are hot & cold in the first, second, third, and fourth degree (which borders on poison), how all these different in their several Tempers, will be made friends in universal misery, and compounded in a general destruction.

Little did either Flowers or Herbs think of the Boares approaching, who were solacing themselves with merry and [39] pleasant discourse; and it will not be amiss to deceive time, by inserting the Courtship of Thrift, a flower-Herb, unto the Marygold, thus accosting her, just as the Boar entered into the Garden.

Mistresse, of all Flowers that grow on Earth, give me leave to profess my sincerest affections to you: Compliments have so infected men's tongues (and grown an Epidemicall fault, or as others esteem it, a fashionable accomplishment) that we know not when they speak truth, having made dissembling their language, by a constant usage thereof: but believe me Mistriss [40] my heart never entertained any other interpreter then my Tongue; and if there be a veine (which Anatomists have generally avouched, carrying intelligence from the heart to the lips) assure your selfe that vein acts now in my discourse.

I have taken signall notice of your accomplishments, and among many other rare qualities, particularly of this, your loyalty and faithfulnesse to the Sun, Sovereign to all Vegetables, to whose warming Beams, we owe our being and increase; such your love thereunto, that you attend his rising, and therewith open, and at his setting shut [41] your windowes: True it is, that Helitropium (or turner with the Sun) hath a long time been attributed to the Sun-flower, a voluminous Giantlike Flower, of no vertue or worth as yet discovered therein, but we all know the many and Soveraign vertues in your leaves, the Herb generall in all pottage: Nor do you as Herb John stand newter, and as too many now adaies in our Commonwealth do, neither good nor ill (expecting to be acted on by the impression of the prevalent party) and otherwise warily engage not themselves; but you really appear soveraign and operative in your [42] wholesome effects: The consideration hereof, and no other by reflection, hath moved me to the tender of my affections, which if it be candidly resented, as it is sincerely offered, I doubt not but it may conduce to the mutual happinesse of us both.

Besides know (though I am the unproperest person to trumpet forth my own praise) my name is Thrift, and my nature answereth thereunto; I do not prodigally wast those Lands in a moment, which the industry and frugality of my Ancestors hath in a long time advanced: I am no gamester to shake away with a quaking hand, what a [43] more fixed hand did gain and acquire: I am none of those who in variety of cloaths, bury my quick estate as in a winding sheet; nor am I one of those who by cheats and deceits improve my selfe on the losses of others; no Widowes have wept, no Orphans have cryed for what I have offered unto them (this is not Thrift but rather Felony) nor owe I anything to my own body; I fear not to be arrested upon the action of my own carcasse, as if my creditors should cunningly compact therewith, and quit scores, resigning their Bill and Bond unto mine own body, whilst that in re[44]quitall surrendereth all obligations for food and cloaths thereunto. Nor do I undertake to buy out Bonds in controversies for almost nothing, that so running a small hazard, I may gain great advantage, if my bargain therein prove successfull. No, I am plain and honest Thrift, which none ever did, or will speak against, save such prodigall spend-thrifts, who in their reduced thoughts, will speak more against themselves.

And now it is in your power to accept or refuse what I have offered, which is the priviledg which nature hath allotted for your feminine sex, which we men [45] perchance may grudge and repine at, but it being past our power to amend it, we must permit ourselves as well as we may to the constant custome prevailing herein.

The Marigold demurely hung down her head, as not overfond of the motion, and kept silence so long as it might stand with the rule of manners, but at last brake forth into the following return.

I am tempted to have a good opinion of my selfe, to which all people are prone, and we women most of all, if we may believe your ------ of us, which herein I am afraid are too true: [46] But Sir, I conceive my selfe too wise to be deceived by your commendations of me, especially in so large a way, and on so generall an account, that other Flowers not only share with me, but exceed me therein: May not the Daies-eye not only be corrivall with me; but superior to me in that quality, wherein so much you praise me; my vigilancy starteth only from the Sun rising, hers bears date from the dawning of the morning, and out-runs my speed by many degrees: my vertue in pottage, which you so highly commend, impute it not to my Modesty, but to my Guiltinesse, if I cannot [47] give it entertainment; for how many hundred Herbs which you have neglected exceed me therein.

But the plain truth is, you love not me for my selfe, but for your advantage: It is Gold on the arrear of my name which maketh Thrift to be my Suitor: how often, and how unworthily have you tendered your affections, even to Penny-royall, it selfe, had she not scorned to be courted by you.

But I commend the Girle that she knew her own worth, though it was but a Penny, yet it is a Royall one, and therefore not a fit match for every base [48] Suitor, but knew how to valew her selfe; and give me leave to tell you, that Matches founded on Covetousnesse never succeed: Profit is the Load-stone of your affections, Wealth the attractive of your Love, Money the mover of your desire; how many hundreds have engaged themselves on these principles, and afterwards have bemoaned themselves for the same? But oh the uncertainty of wealth! how unable it is to expleate and satisfy the mind of man: Such as cast Anchor thereat, seldom find fast ground, but are tossed about with the Tempests of many disturbances: these Wives for con[49]veniency of profit and pleasure (when there hath been no further nor higher intent) have filled all the world with mischief and misery. Know then Sir, I return you a flat deniall, a deniall that vertually contains many, yea, as many as ever I shall be able to pronounce: My tongue knowes no other language to you but No; score it upon womens dissimulation (whereof we are too guilty, and I at other times as faulty as any) but Sir, read my eyes, my face, and compound all together, and know these are the expressions dictated from my heart; I shall embrace a thousand deaths [50] sooner, then your Marriage-Bed.

Thus were they harmelessly discoursing, and feared no ill, when on a sudden they were surprized with the uncouth sight of the Boare, which had entered their Garden, following his prescribed directions, and armed with the Corslet of his Bristles, vaunted like a triumphant Conqueror round about the Garden, as one who would first make them suffer in their fear, before in their feeling; how did he please himselfe in the variety of the fears of the flowers, to see how some pale ones looked red, and some red [51] ones looked pale; leaving it to Philosophers to dispute and decide the different effects should proceed from the same causes; and among all Philosophers, commending the question to the Stoicks, who because they pretend an Antipathy, that they themselves would never be angry, never be mounted above the modell of a common usuall Temper, are most competent Judges, impartially to give the reason of the causes of the anger of others.

And now it is strange to see the severall waies the Flowers embraced to provide for their owne security; there is no such [52] Teacher as extremity; necessity hath found out more Arts, then ever ingenuity invented: The Wall-Gilly flower ran up to the top of the Wall of the Garden, where it hath grown ever since, and will never descend till it hath good security for its own safety; and being mounted thereon, he entertained the Boar with the following discourse.

Thou basest and unworthiest of four-footed Beasts; thy Mother the Sow, passeth for the most contemptible name, that can be fixed on any She: Yea, Pliny reporteth, that a Sow growne old, useth to feed on her owne [53] young; and herein I beleeve that Pliny, who otherwise might be straitned for fellow-witnesses, might find such who will attest the truth of what he hath spoken. Mens Excrements is thy element, and what more cleanly creatures do scorn and detest, makes a feast for thee; nothing comes amisse unto thy mouth, and we know the proverb what can make a pan-cake unto thee: Now you are gotten into the Garden (shame light on that negligent Gardner, whose care it was to fence the same, by whose negligence and oversight, you have gotten an entrance into this Academy of Flowers and [54] Herbs) let me who am your enemie give you some Counsell, and neglect it not, because it comes from my Mouth. You see I am without the reach of your Anger, and all your power cannot hurt me, except you be pleased to borrow wings from some Bird, thereby to advantage your selfe, to reach my habitation.

My Counsell therefore to you is this, be not Proud because you are Prosperous; who would ever have thought, that you could have entered this place, which we conceived was impregnable against any of your kind: Now because you [55] have had successe as farre above our expectations, as your deserts; show your own moderation in the usage thereof; to Master us is easie, to Master your selfe is difficult. Attempt therefore that which as it is most hard to performe, so will it bring most honour to you when executed; and know, I speak not this in relation to my selfe (sufficiently priviledged from your Tusks) but as acted with a publique spirit, for the good of the Comminalty of Flowers; and if any thing hereafter betide you, other then you expect, you will remember that I am a Prophet, and foretell that which too late [56] you will credit and believe.

The Boar heard the words, and entertained them with a surly silence; as conceiving himselfe to be mounted above danger, sometimes he pittied the sillinesse of the Wall-flower, that pittyed him, and sometimes he vowed revenge, concluding that the stones of the Wall would not afford it sufficient moisture, for its constant dwelling there, but that he should take it for an advantage, when it descended for more sustenance.

It is hard to expresse the panick fear in the rest of the flowers, and especially the small [57] Prim-roses, begged of their Mothers that they might retreat into the middle of them, which would only make them grow bigger and broader, and it would grieve a pittifull heart to hear the child plead, and the mother so often deny.

The Child began; dear Mother, she is but halfe a Mother that doth breed and not preserve, only to bring forth, and then to expose us to worldly Misery, lessens your Love, and doubles our sufferings: See how this tyrannicall Boare threatens our instant undoing; I desire only a Sanctuary in your bosome, a retreating place into your breast, [58] and who fitter to come into you, then she that came out of you; whether should we return, then from whence we came, it will be but one happinesse, or one misfortune, together we shall die, or together be preserved; only some content and comfort will be unto me, either to be happy or unhappy in your company.

The broader Prim-rose hearkned unto these words with a sad countenance, as sensible in her selfe, that had not the present necessity hardned her affections, she neither would nor could return a deaf eare to so equall a motion. But now she rejoyned.

[59] Dear Child, none can be more sensible then my selfe of Motherly affections, it troubles me more for me to deny thee, then for thee to be denyed; I love thy safety where it is not necessarily included in my danger, the entertaining of thee will be my ruine and destruction; how many Parents in this age have been undone meerly for affording house and home to such Children, whose condition might be quarrel'd with as exposed to exception.

I am sure of mine owne innocency, which never in the least degree have offended this Boar, and therefore hope he will not [60] offend me; what wrong and injury you have done him is best known to your selfe; stand therefore on your own bottome, maintain your own innocence; for my part I am resolved not to be drowned for others hanging on me, but I will try as long as I can the strength of my own armes and leggs; excuse me good child, it is not hatred to you, but love to my selfe, which makes me to understand my own interest. The younger Prim-rose returned.

Mother, I must again appeal to your affections, despairing to find any other Judge to Father my cause; remember I am part [61] of your selfe, and have never by any undutifulnesse disobliged your affections; I professe also mine own integrity, that I never have offended this Boar, being more innocent therein then your selfe, for alas my tender years intitles me not to any correspondency with him, this is the first minute (and may it be the last) that ever I beheld him; I reassume therefore my suite, supposing that your first denyall proceeded only from a desire to try my importunity, and give me occasion to enforce my request with the greater earnestnesse: By your motherly bowels I conjure you (an exor[62]cisme which (I beleeve) comes not within the compasse of superstition) that you tender me in this my extremity, whose greatest ambition is to die in those armes from whence I first fetcht my originall. And then she left her tears singly to drop out the remainder, what her tongue could not expresse.

The Affections of Parents may sometimes be smothered, but seldome quenched, and meeting with the blast or bellowes from the submissive mouthes of their Children, it quickly blazeth into a flame. Mother and daughter are like Tallies, one exactly answereth the other: The Mo[63]ther Prim-rose could no longer resist the violence of her daughters importunity, but opens her bosome for the present reception thereof, wherein ever since it hath grown doubled unto this day; and yet a double mischief did arise from this gemination of the Print-rose, or inserting of the little one into the Bowels thereof.

First, those Prim-roses ever since grow very slowly, and lag the last among all the Flowers of that kind; single Prim-roses beat them out of distance, and are arrived at their Mark a month before the other start out of their green leaves: yet it [64] will not be hard to assigne a naturall cause thereof, namely, a greater power of the Sun is acquired to the production of greater Flowers, small degrees of heat will suffice to give a being to single Flowers, whilst double ones groaning under the weight of their own greatnesse, require a greater force of the Sun-beams to quicken them, and to spurre their lazinesse, to make them appear out of their roots.

But the second Mischief most concernes us, which is this, all single Flowers are sweeter, then those that are double; and here we could wish that a Jury of [65] Florists were impannelled, not to eat, untill such time as they were agreed in their verdict, what is the true cause thereof. Some will say that single leaves of Flowers, being more effectually wrought on by the Sun-Beams, are rarified thereby, and so all their sweetnesse and perfume the more fully extracted; whereas double Flowers who lie as it were in a lump, and heap crouded together with its own leaves, the Sun-beams hath not that advantage singly to distill them, and to improve every particular leaf to the best advantage of sweetnesse: This sure I am, that the old Prim[66]rose sencible of the abatement of her sweetnesse, since she was clogged with the entertainment of her Daughter, halfe repenting that she had received her, returned this complaining discourse.

Daughter, I am sencible that that the statutes of inmates, was founded on very good and solid grounds, that many should not be multiplyed within the roof of one and the same house, finding the inconveniency thereof by lodging thee my owne Daughter within my Bosome; I wil not speak how much I have lost of my grouth, the Clock whereof is set back a whole [67] month by receiving of you; but that which most grieveth me, I perceive I am much abated in my sweetnesse (the essence of all Flowers) and which only distinguisheth them from weeds, seeing otherwise in Colours, weeds may contest with us in brightnesse and variety.

Peace Mother (replyed the small Prim-rose) conceive not this to be your particular unhappinesse, which is the generall accident falling out daily in common experience, namely, that the bigger and thicker people grow in their estates, the worse and lesse vertuous they are in their Conversations, our [68] age may produce millions of these instances; I knew some tenne years since many honest men, whose converse was familiar and faire, how did they court and desire the company of their neighbours, and mutually, how was their company desired by them? how humble were they in their carriage, loving in their expressions, and friendly in their behaviour, drawing the love and affections of all that were acquainted with them? But since being grown wealthy, they have first learnt not to know themselves, and afterwards none of their neighbours; the brightnesse of [69] much Gold and Silver, hath with the shine and lustre thereof so perstringed and dazled their eyes, that they have forgotten those with whom they had formerly so familiar conversation; how proudly do they walk? how superciliously do they look? how disdainfully do they speak? they will not know their own Brothers and kindred, as being a kin only to themselves.

Indeed such who have long been gaining of wealth, and have slowly proceeded by degrees therein, whereby they have learnt to mannage their minds, are not so palpably proud as others; but those who [70] in an instant have been surprized with a vast estate, flowing in upon them from a fountain farre above their deserts, not being able to wield their own greatnesse, have been prest under the weight of their own estates, and have manifested that their minds never knew how to be stewards of their wealth, by forgetting themselves in the disposing thereof.

I beleeve the little Prim-rose would have beee longer in her discourse, had not the approach of the Boar put an unexpected period thereunto, and made her break off her speech before the ending thereof.

[71] Now whilst all other flowers were struck into a panick silence, only two, the Violet, and the Marygold continued their discourse, which was not attributed to their valour or hardinesse above other Flowers, but that casually both of them grew together in the declivity of a depressed Valley, so that they saw not the Boar, nor were they sensible of their own misery, nor durst others remove their stations to bring them intelligence thereof.

Sister Marigold (said the Violet) you and I have continued these many daies in the contest which of our two colours are [72] the most honourable and pleasing to the Eye, I know what you can plead for your selfe, that your yellownesse is the Livery of Gold, the Soveraign of most mens hearts, and esteemed the purest of all mettals; I deny not the truth hereof: But know that as farre as the Skie surpasseth that which is buried in the Bowels of the Earth, so farre my blew colour exceedeth yours; what is oftner mentioned by the Poets then the azure Clouds? let Heraulds be made the Vmpire, and I appeal to Gerrard, whether the azure doth not carry it cleer above all other colours herein; Sable or [73] Black affrights the beholders with the hue thereof, and minds them of the Funerall of their last friends, whom they had interred[.] Vert or Green I confesse is a colour refreshing the sight, and wore commonly before the eyes of such who have had a casuall mischance therein, however, it is but the Livery of novelty, a young upstart colour, as green heads, and green youth do passe in common experience. Red I confesse is a noble colour, but it hath too much of bloodinesse therein, and affrighteth beholders with the memory thereof: My Blew is exposed to no cavills and exceptions, [74] wherein black and red are moderately compounded, so that I participate of the perfections of them both: the over gaudinesse of the red, which hath too much light and brightness therein, is reduced and tempered with such a mixture of black, that the red is made stayed, but not sad therewith, and the black kept from over-much melancholy, with a proportionable contemperation of red therein: This is the reason that in all ages the Violet or purple colour hath passed for the emblem of Magistracy, and the Robes of the antient Roman judges [were] alwaies died therewith.

[75] The Violet scarce arived at the middle of her discourse, when the approach of the Boar put it into a terrible fear, nor was their any Herb or Flower in the whole Garden left unsurprized with fear, save only Time and Sage, which casually grew in an island surrounded with water from the rest, and secured with a lock-bridge from the Boars accesse. Sage beginning, accosted Time in this Nature.

Most fragrant Sister, there needs no other argument to convince thy transcendent sweetnesse, save only the appealing to the Bees (the most [76] competent judges in this kind) those little Chymists, who through their natural Alembick, distill the sweetest and usefullest of Liquors, did not the commonnesse and cheapnesse thereof make it lesse valued: Now these industrious Bees, the emblem of a common-wealth (or Monarchy rather, if the received traditions of a Master-Bee be true) make their constant diet upon the[e]; for though no Flower comes amisse to their palates, yet are they observed to preferre thee above the rest. Now Sister Time, faine would I be satisfied of you severall queries, which only Time [77] is able to resolve. Whether or no do you think that the State of the Turks wherein we live, (whose cruelty hath destroyed faire Tempe to the small remnant of these few Acres) whether I say, do you think that their strength and greatness doth encrease, stand still, or abate? I know Time that you are the Mother of truth, and the finder out of all truths mysteries; be open therefore and candid with me herein, and freely speak your mind of the case propounded.

Time very gravely casting down the eyes thereof to the earth; Sister Sage (said she) had you propounded any question [78] within the sphear or circuit of a Garden, of the heat or coolnesse, drinesse or moisture, vertue or operation of flowers and Herbs, I should not have demurred to return you a speedy answer; but this is of that dangerous consequence, that my own safety locks up my lips, and commands my silence therein: I know your wisdome Sage, whence you have gotten your name and reputation, this is not an age to trust the neerest of our relations with such an important secresie; what ever thoughts are concealed within the Cabinet of my own bosome, shall there be preserved in their secret pro[79]pertie without imparting them to any; my confessor himselfe shall know my conscience, but not my judgement in affaires of State: Let us comply with the present necessity, and lie at a close posture, knowing there be fencers even now about us, who will set upon us if our guards lye open: generall discourses are such to which I will confine my selfe: It is antiently said, that the subtill man lurks in generall. But now give me leave, for honesty it selfe, if desiring to be safe, to take Sanctuary therein.

Let us enjoy our own happinesse, and be sensible of the [80] favour indulged to us, that whereas all Tempe is defaced, this Garden still surviveth in some tolerable condition of prosperity, and we especially miled [for isled?] about, are fenced from forraign foes, better then the rest; let it satisfie your soule that we peaceably possess this happinesse, and I am sorry that the lustre thereof is set forth with so true a foile, as the calamity of our neighbours.

Sage returned; Were I a blab of my mouth, whose secresie was ever suspected, then might you be cautious in communicating your mind unto me: But secrecy is that I can principally [81] boast of, it being the quality for which the common-wealth of Flowers chose me their privy Councellor, what therefore is told me in this nature, is deposited as securely, as those treasures which formerly were laid up in the Temple of safety it self; and therefore with all modest importunity, I reassume my suit, and desire your judgment of the question, whether the Turkish Tyranny is likely to continue any longer? for Time I know alone can give an answer to this question.

Being confident (said Time) of your fidelity, I shall expresse my selfe in that freenesse unto [82] you, which I never as yet expressed to any mortall: I am of that hopefull opinion, that the period of this barbarous nations greatnesse begins to approach, my first reason is drawn from the vicissitude and mutability which attends all earthly things; Bodies arrived at the verticall point of their strength, decay and decline. The Moon when in the fulnesse of its increasing, tendeth to a waning; it is a pitch too high for any sublunary thing to amount unto constantly, to proceed progressively in greatnesse; this maketh me to hope that this Giant-like Empire, comented [83] with Tyranny, supported, not so much with their own policy, as with the servility of such who are under them, hath seen its best daies and highest elevation.

To this end, to come to more particulars, what was it which first made the Turks fortunate, in so short a time to over-run all Greece, but these two things; first, the dissentions, 2. the dissolutenesse of your antient Greeks: Their dissentions are too well known, the Emperor of Constantinople being grown almost but titular, such the pride and potency of many Peeres under him. The Egean is not [84] more stored with Islands (as I think scarce such a heap or huddle is to be found of them in all the world againe) as Greece was with severall factions, the Epirots hated the Achayans, the Mesedans bandoned against the Thracians, the Dalmatians maintained deadly feud against the Wallachians: Thus was the conquest made easie for the Turks, beholding not so much to their own valour, as to the Grecian discord.

Next to their dissentions, their dissolutenesse did expedite their ruine; drunkennesse was so common among them, that it was a sin to be sober, so that I [85] may say, all Greece reel'd and staggered with its own intemperance when the Turk assaulted it: What wonder then was it if they so quickly over-ran that famous Empire, where vice and lazinesse had generally infected all conditions of people.

But now you see the Turks themselves have divisions and dissentions among them, their great Bashaws and holy Muftees have their severall factions and dissentions; and whereas the poor Greeks by the reason of their hard usage, begin now to be starved into unity and temperance, they may seem to have changed their vices with the [86] Turks, who are now grown as factious and vitious as the other were before. Adde to all this that they are universally hated, and the neighbouring Princes raither wait a time, then want a will to be revenged on them for their many insolencies. Put all these together, and tell me if it put not a cheerfull complexion on probability, that the Turkish tyranny having come to the mark of its own might, and utmost limits of its own greatnesse, will dwindle and wither away by degrees. And assure your selfe, if once it come to be but standing water, it will quickly be a low ebb with them.

[87] Probably she had proceeded longer in her Oration, if not interrupted with the miserable moanes and complaints of the Herbs and Flowers which the Boar was ready to devour, when presently the Sage spake unto the Boar in this manner.

Sir, Listen a little unto me, who shall make such a motion whereof your selfe shall be the Judge (how much it tendeth to your advantage, and the deafest ears will listen to their own interest.) I have no designe for my selfe (whose position here invironed with water, secureth [88] me from your anger) but I confesse I sympathize with the miserie of my friends and acquaintance, which in the continent of the Garden are exposed to your cruelty; what good will it do you to destroy so many Flowers and Herbs, which have no gust or sweetnesse at all in them for your palate; follow my directions, and directly South-west as you stand, you shall find (going forward therein) a corner in the Garden, overgrown with Hog-weed, (through the Gardiners negligence;) Oh what Lettice will be for your lipps; you will say that Via lactea (or the milkie way) is [89] truly there, so white, so sweet, so plentifull a liquor is to be distilled out of the leaves thereof, which hath gotten the name of Hog-weed, because it is the principall Bill of fare whereon creatures of your kind make their common repast. The Boar sensible that Sage spake to the purpose, followed his directions, and found the same true, when feeding himselfe almost to surfet on those delicious dainties, he swelled so great, that in his return out of the Garden, the hole in the fence which gave him admittance, was too small to afford him egress out thereat; when the Gardiner [90] coming in with a Guard of Dogs, so persecuted this Tyrant, that killed on the place, he made satisfaction for the wrong he had done, and for the terrour wherewith he had affrighted so many Innocents. I wish the Reader well feasted with some of his Brawn well cooked, and so take our leave both of him and the Gardens.

Back to Critical Headnote